Many U.S. separatist religious or cultural sects have seen their numbers diminish or die out. In fact, in a short follow-up to this posting in a couple of days, I’ll tell you about two of them.

But some remarkably plain people who wear what must be uncomfortably hot outfits as the American summer nears, and whose lifestyle moves as fast as, well, a horse and buggy, are flourishing. The number of Old Order Amish has doubled since 1992 and jumped by 10 percent in the past two years, to an estimated total of 250,000 people, many far from their traditional strongholds in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. In fact, you’ll find Amish farmsteads in 28 of the 50 U.S. states, and Amish “scouts” have been spotted in far-off Alaska and Mexico as well.

The Amish boom is happening not just because these people, who seem out of place, even odd, in these days of casual dress, social networking, permissive moral attitudes and an abundance of modern conveniences, have large families. That’s a big part of it, though. The Amish don’t practice birth control, and most of their families have five or more children, and broods of seven or eight — even 15! — are not unusual.

Other reasons for the move into new territory: Development, including tract houses and shopping centers, is encroaching on their traditionally isolated rural territory, bringing a measure of chaos, clutter, and sinful temptations for Amish young people, in particular. Amish men and women grow tired of being tourist attractions, a curiosity to be approached, photographed, even asked by “English” travelers — the Amish call outsiders “English,” or Englischers in German, because of their language — to pose for stupid souvenir photographs, when the Amish eschew photographs as vain.

A horse and buggy approach, as safely off the high-speed portion of the road as possible. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Distant shots don’t seem to disturb them, though, and anyway, the most you’ll get for popping one is a shaken fist, since the Amish don’t believe in lawsuits! You’ll note an Amish face or two in the photos that accompany this posting, but it’s a historic photo or one of Carol’s shots respectfully taken from a ways away.

The Amish refer to themselves as “Dutch.” Wherever they live, the Plain People are often called “Pennsylvania Dutch,” corrupted from the word Deutsch — the German language. Old Order Amish are in fact trilingual: They speak High German at worship; English at school and in dealing with the Englischers; and, at home, a German dialect peppered with words borrowed from English and softened by French influences from their people’s time in Alsace.

Like it or not, Old Order Amish’s distinctive 19th-century lifestyle must endure alongside, and within, the 21st-century world. These people cheerfully acknowledge that they are living in a time warp as they drive horse-drawn buggies, open carts, and mule- or horse-pulled farm machinery. Their farms are often the largest, best-kept, and most prosperous in their counties.

Lush fields, sturdy barns, clothes on the line at this Amish farm, and not an electrical wire to be found. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Their homesteads are characterized by well-manicured gardens, windmills, and long rows of hanging wash on clotheslines, as well as one, two, or more additions to their farmhouses to accommodate the old folks, who remain in the household until they die.

But what makes these places especially easy to spot are the plain window shades — that “plain” word again — and the absence of electric wires, frilly curtains, or any other kind of adornments.

“Amish Country” is a serene place, full of rolling meadows, vibrant fields of corn and grain, and the Amish people’s tidy farmsteads. Serene, that is, unless you’re stuck behind lines of tourists’ cars, funneling into quaint villages with even quainter names: Bird-in-Hand, Intercourse, and Blue Ball, for instance, in Pennsylvania; and Charm, Birds Run, Nellie, and Blissfield in Ohio.

Whoopie pies are not pies but soft chocolate, vanilla, or oatmeal cakes overstuffed with creamy pudding. (Carol M. Highsmith)

There, you can ride in Amish buggies, gorge yourself at smorgasbord restaurants and Amish bakeries — just try eating a couple of whoopee pies and then tell me the Amish aren’t sinful! — and watch Amishmen make furniture and cheese. Their establishments, though, are often staffed out front in public areas, by “English” employees.

Despite the Amish people’s desire for a respect for their privacy, the men with beards and straw hats and women in bonnets, not to mention their ubiquitous horses and buggies (and horsedrawn hearses) can’t help but be a curiosity.

So unlike odd societies that keep their distance, the Amish are not separatists. They do not live in communes. Their handsome farms are spread alongside those of their non-Amish neighbors. The most noticeable difference is that their neighbors will plow their fields with motorized tractors, while the Amishman — or just as often, the Amish boy — will plow his with a team of draft horses or mules. Tobacco and cattle were once the Amish farmer’s chief commodities. These days, it’s dairy cattle, corn, and soybeans.

The demand for land is growing so great that Amish farmers as well as non-Amish developers routinely bid against each other for available parcels. Since the Amish live simply and frugally, the wealthy among them do not spend their money on baubles, cruises, or fancy homes; they buy more land! And they put their money in the bank to save for future generations. The Amishmen are also always in search of more land to meet their obligation to provide farms for their male offspring. Hence another reason they check out the farmlands of Kansas, Texas, Montana and beyond.

Wherever they go, the Amish keep in touch through a chatty newspaper called The Budget, published in Sugarcreek, Ohio. Its news is anything but scandalous, for sure. For instance, this hot new reported development:

The spring peppers are really enjoying this fine weather, their first outing, and during the day the chirping sparrows’ song fills the air.

The current U.S. recession has not entirely bypassed the Amish. Many of their young people, working in stores and factories in town, have been laid off. And sales of Amish people’s goods have dropped commensurately with a decline in consumer spending. But there’s no such thing as a homeless Amishman. There’s always a large and welcoming place to go home to.

“Old Order” Amish are the hard-core traditionalists. There are also “New Order” or “Beachy,” Amish — named for Amishman Moses Beachy from Pennsylvania, who led a walkout from an Amish community over the issue of shunning. (More about that in a bit.) Beachy Amish have incorporated some vestiges of modern technology, sometimes even driving cars — albeit black ones with plain black bumpers.

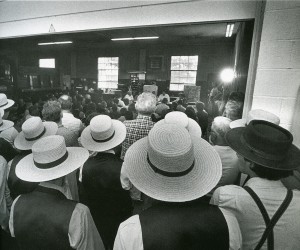

Amishmen listen in on a meeting about a proposed subdivision of a local farm into hundreds of housing plots. (Free Library of Philadelphia)

To further confuse visitors, members of strict Mennonite orders also drive buggies and eschew electric appliances in their homes. And many Mennonite men wear beards and plain clothing.

They and the Amish are part of the Anabaptist movement, which began in Switzerland in the early 1500s at the time of the Protestant Reformation. The name means “twice baptized,” as their members — already baptized into the Roman Catholic Church as infants — were anointed a second time as adults. Later, Anabaptists rejected infant baptism, believing that the individual should make a free choice to accept a life with God. At that time, adult baptism was considered a criminal offense that was punishable by death, and many Anabaptists were imprisoned and tortured for their beliefs.

Amish songs and books keep stories of their persecution alive and contribute to ongoing Amish distrust of society at large. A favorite Amish story tells the fate of a Dutch Anabaptist who pulled to safety a pursuing sheriff who had fallen through the ice on a pond. For his kindness, the Anabaptist was arrested and burned at the stake.

One of the reasons Amishmen wear no moustaches dates to this period, for the soldiers who tormented them often wore long, florid ones.

To avoid detection, Anabaptists fled to the mountains or distant rural regions, where many became farmers. In 1693, Anabaptists in the Alsace region, now part of France, broke away from the larger church. Jakob Ammann, their leader, believed the Anabaptists had become too liberal in their lifestyles, straying from strict biblical teachings. Ammann’s followers became known as the Amish, and Swiss Anabaptists as the Mennonites, a name derived from their leader, Menno Simons.

In the early 1700s, the Amish accepted the invitation of William Penn, Pennsylvania’s founder, to Europeans of all religions to come to “Penn’s Woods” and enjoy a life of freedom and religious tolerance. True to their history once they arrived, the Amish promptly headed far into what was then the wilderness, where the “world” could not follow.

No Amish congregations remain in Europe.

There are no Amish church buildings and no religious icons other than the Bible — an edition originally translated into German by Protestant reform leader Martin Luther. There’s no special Amish creed aside from following Christ’s example by living simply and humbly and helping others. Even personal Bible study is discouraged because it might lead to individual interpretations outside the accepted understanding of God’s word.

The Amish believe that working the soil brings them close to God. Worship services are held every other Sunday in each other’s homes. Thus Old Order Amish are sometimes called “House Amish.” In rooms cleared of household furniture, men and boys sit on one side, and women and girls on the other, both facing a central area where leaders are seated.

The 3½-hour service begins with about 35 minutes of singing from the Ausbund, an 812-page German-language hymnal written by Anabaptists while they were imprisoned in the 1530s. No instruments accompany the singing, which is delivered slowly in a chant with no harmony. Believe it or not, some hymns have as many as 60 verses! It’s worth the wait, though. Verse 58 is a pip.

The service is followed by ritual foot-washing and the sharing of bread and wine, the latter made from grapes by the bishop’s wife.

The Amish exchange small, practical gifts at Christmas, but there are no Christmas trees, lights, or Santa Claus figures, stories or songs. Nor does Peter Cottontail hop down the bunny trail around Easter in Amish country. Bunnies are sometimes served at mealtime, however.

Sunday afternoons are a time for play and socializing. Young singles, who, together, are called “gangs” by the Amish, travel to other homes on Sunday evenings for more hymn-singing. A “date” will often consist of singing hymns — you may be detecting a trend here — or perhaps a spirited game of volleyball. It is to and from these events that a young Amishman will often drive a single Amishwoman in an open “courting buggy.”

In communities with large Amish populations, enclosed family buggies, sometimes laughingly called “cheese boxes” by the Amish themselves, must have lights and triangular rear reflectors. These are meager protection against onrushing automobiles, although the Amish keep to the side of the road whenever possible. Nevertheless, there are many gruesome accidents in which the Amish and their horses almost always get the worst of it.

Amish elders often look the other way as many of their young people “sow their wild oats” and taste worldly pleasures for a period. In this time of modest rebellion, it is not uncommon for Amish teenagers and young adults to obtain driver’s licenses and drive cars, change from their simple clothes into Englischer garb, and go dancing and bar-hopping in big cities. Such rascally behavior is tolerated because the young people have not yet joined the church.

But once a person accepts baptism — often at the time of marriage — all such worldly dalliances are banned forever. The penalty for deviation is lifetime shunning by the community — parents and siblings included. The excommunicated person may remain with his or her Amish spouse, but sexual relations are forbidden until and unless he or she renounces wicked behavior and returns to the fold.

Elizabethtown College professor Donald Kraybill, who has written several long backgrounders on the Amish, told me that four of five young Amish people accept baptism and remain in the fold. After all, temptations to stay are surprisingly strong. Within the community there is love, support, security, and what I would call a degree of certainty that the harsh “real world,” with its scary twists and torments, cannot guarantee.

Marriage is encouraged by the Amish but by no means expected. Unmarried Amishmen work farms or get jobs as carpenters, buggy makers, or mill employees. Amishmen are enthusiastic participants in volunteer fire departments, whose efforts obviously benefit Amish homes and barns. But the Amish do not participate in other organizations, organized sports, or political parties. Amishmen will not serve in military services; in wartime, they have traditionally been exempted from service as conscientious objectors and given noncombat roles.

Amish canned goods are yummy and are usually snapped up quickly when sold in town. (Carol M. Highsmith)

The Amish bank at town financial institutions, and they hold public auctions. Unmarried Amish women often leave home to run quilt, bake, or craft shops, or to work in Amish butcher shops or health-food stores. Married Amish women also sometimes work outside the home, and two-income Amish households are becoming almost as common as in the community at large.

Obedience — children to parents and teachers, wives to husbands, and all to God’s word — is central to the Amish way of life. So is the glorification of God and the community, not the individual. Arrogance, pride, publicity, and adornments that call attention to oneself are forbidden. You won’t see Amish people with nose rings, tattoos, or Facebook pages.

Unmarried men are clean-shaven, and boys often are given bobbed “Dutch cut” haircuts. Married men grow beards, which, for the rest of their lives, they never trim. They wear straw hats to keep the sun off their necks in warm weather but switch to black felt hats for worship and on cold days. Amish girls and women wear prayer coverings at all times in public due to a biblical dictate from 1st Corinthians.

Amish homes are generally devoid of decoration, although the Plain People will hang calendars, dried flowers, colorful quilts, and photographs — of scenery, never themselves or others.

Often the kitchen is the only heated room in an Amish house, and the sick are sometimes tended to there. Most kitchens do have modern-looking appliances such as refrigerators and washing machines — run by kerosene or propane gas.

The aversion to electricity has nothing to do with the modernity of it all, and certainly the Bible was silent on the practical use of electrons. Rather, the objection is that wires from the street into the house or barn are a tangible tie to the outside world that the Amish wish to avoid. Many bishops allowed telephones in Amish homes for a time, though, until people were found to be gossiping; pay phones can now be found at the end of country lanes.

You won’t find Amish people going door to door looking for converts. They believe that their good works and piety speak for themselves. They welcome converts, but Englischers find it difficult to renounce modern conveniences (“No iPod? You’ve got to be kidding”). Potential converts find it especially wrenching to give up their automobiles.

Life isn't easy for this Amishwoman, but it's got to be easier than that of her horses and mules. (Carol M. Highsmith)

You’ll find powerful mechanized equipment on the farm and in mills, but it’s run by steam, not internal-combustion engines, and is pulled by draft animals just like farm wagons. The Amish do, however, accept rides, and “English” taxi services do a lively business. The Amish will also hire non-Amish drivers to move products and take them to visit far-off relatives. Train and intercity bus travel is allowed, but air travel is rarely permitted.

Amish children may attend public school, but more common in heavily Amish areas are one-room, English-language parochial schools where, once again, boys and girls are separated by a middle aisle. It was such a school in Bart Township, Pennsylvania, that brought worldwide attention to the reclusive Amish in 2006, when a deranged non-Amish gunman shot and killed six girls after lining them up against a chalkboard. What staggered the outside world even more than the heinous act was the Amish response. An Amish neighbor comforted the killer’s wife and children, and the Amish set up a charitable fund for them and offered them the community’s forgiveness.

The Amish are plain, not perfect, people. They cling stubbornly to old ways, resist new ones, and keep to themselves. There are jealousies and feuds as in any community. Births out of wedlock, mental illness, family violence, and suicide are not unknown among them. But the Amish by all accounts are also loving and supportive, though strict, parents. Their homes are “safe houses” for old and young. The “information age” may be passing the Amish by, but so are many of the stresses and dangers that grip the outside world. The Amish can and do fairly ask of their worldly neighbors, “Where is all your ‘progress’ taking you? Are you happier? More loved? More fulfilled?”

Note the simplicity and effective air flow of this Amish corn crib. (Carol M. Highsmith)